This story was originally published by MinnPost.

A decade ago, when news broke that zebra mussels had found their way to Cass Lake, I was dismayed but not surprised. Since escaping from the ballast of an ocean-going vessel in Lake Superior sometime in the late 1980s, the invasive shellfish have spread relentlessly throughout Minnesota’s waters.

Cass Lake, where I have frolicked and fished since childhood, was obviously vulnerable. With its famously robust population of walleye, yellow perch and muskellunge, the 16,000-acre lake — located in the Chippewa National Forest, about 15 miles east of Bemidji — has long been a destination for recreational anglers. It felt like a matter of time before the troublesome bivalves hitched a ride on someone’s boat.

In the years since zebra mussels arrived, the changes in the lake have been impossible to miss. Most strikingly, the once green-hued waters have become gin clear, a consequence of the dime-sized filter-feeders’ prodigious capacity to hoover up plankton and reproduce at astonishing rates.

In one regard, I have enjoyed this transformation. On certain still, sunny days, the lake is now an aquarium, with schools of big fish plainly visible as they cruise the edges of drop-offs and weed lines. Sometimes, the water is so clear you can make out the distinctive white patch on the tail fin of walleye ten feet deep. Prior to the invasion, I never saw that.

At first, like many anglers at Cass Lake, I feared that the zebra mussels would ruin the fishing. That has not happened. On the contrary, as time passed, and the mussels encrusted virtually every submerged stick, rock and clam in the shallows, the fishing on Cass Lake has remained good.

According to the annual fishery surveys of Cass Lake conducted by the Department of Natural Resources, for reasons that are not clear, both walleye and perch appear to be thriving in the wake of the zebra mussel invasion.

So what’s not to love?

As it turns out, a lot.

At the same time the mussels have made the water clearer, they have deposited a layer of silty waste on the lake bottom. I have noticed this changed substrate while wading in the shallows. Areas that were once characterized by a firm, sandy bottom are now soft. When your feet sink into the muck, a plume billows around them.

This sediment is a combination of zebra mussel feces and undigested material referred to as pseudo feces. And it is now thought to play a key role in dramatically higher rates of methylmercury found in the walleyes and perch that swim in invaded waters.

According to the annual fishery surveys of Cass Lake conducted by the Department of Natural Resources, for reasons that are not clear, both walleye and perch appear to be thriving in the wake of the zebra mussel invasion. It works like this: Inorganic mercury in the atmosphere — largely the product of human activities such as coal burning and gold mining — is deposited in lakes by rain. While inorganic mercury is a potent neurotoxin, it doesn’t enter the food web until it is transformed into an organic form, methylmercury.

That process — methylation — is accelerated by the microbial communities that flourish in the low oxygen environment found in that layer of zebra mussel waste. The methylmercury is ingested by small organisms, which in turn are consumed by larger ones, including fish. The further up the food chain, the more methylmercury accumulates, a process referred to as biomagnification (and the reason that government fish consumption advisories generally encourage people to eat smaller fish).

In a study published in the December issue of the academic journal Science of The Total Environment, researchers from the University of Minnesota, the Department of Natural Resources, the U.S. Geological Survey and other agencies collected walleye and perch from 21 Minnesota lakes — 12 infested with zebra mussels, nine uninvaded — and then tested for mercury.

The results of the three-year survey are alarming: In lakes with zebra mussels, mercury levels in walleyes were found to be on average 72 percent higher than in walleyes from uninvaded lakes. For perch, the number is an astonishing 157 percent.

“That was a very big surprise to all of us. It speaks to how powerful this effect from zebra mussels is,” said biologist Naomi Blinick, a University of Minnesota researcher and co-author of the study. “Zebra mussels are called ecosystem engineers, and they are. They change the very nature of our lakes.”

When Blinick started her research, methylmercury was not her main concern. She was more interested in investigating how zebra mussel invasions alter fish feeding behavior, in particular how walleye and perch rely more heavily on shallow waters because of mussel-induced changes to the food web.

Her study confirmed that the fish from invaded lakes were indeed getting more of their food from near shore waters. But when worrisome mercury results started coming in, the focus shifted and the study was expanded from 12 lakes to 21. (Zebra mussels aside, mercury levels vary between bodies of water, so Blinick and her colleagues wanted to make sure the lakes in the study shared basic ecological characteristics, making for an apples-to-apples comparison.)

What do these findings mean for human health?

In lakes with zebra mussels, mercury levels in walleyes were found to be on average 72 percent higher than in walleyes from uninvaded lakes. In its fish consumption guidelines, the Minnesota Department of Health says sensitive groups — women of childbearing age and children under 15 — should eat no more than one fish meal a month once mercury levels exceed .22 parts per million.

In invaded lakes, the study found, walleye typically reach that threshold by the time they are 14-inches long. When a walleye from invaded waters reached what many consider a prime size for the table – 16.5 inches – the median level of mercury was .30 parts per million. In uninvaded lakes, by contrast, walleye grew to be 18 inches before hitting the .22 parts per million threshold.

For perch, a fish long regarded as a best choice for table fare owing to its low spot in the food chain, the results were also discouraging. In invaded lakes, perch were found to exceed the .22 parts per million threshold once they reached a length of 8.8 inches. In uninvaded lakes, the study found, the likelihood of an adult perch exceeding that threshold was “near zero.”

In Blinick’s view, such findings highlight the importance of considering a lake’s zebra mussel status when choosing what fish to eat. In a statement, Angela Preimesberger, the Department of Health’s fish consumption guidance scientist, said the agency would include the data from the study as it updates its lake-specific recommendations.

At Upper and Lower Red Lake in north central Minnesota, home of the Red Lake Band of Chippewa Indians, the threat of the zebra mussel invasion is a subject of heightened concern. The tribe operates the only commercial walleye fishery in the state and many band members rely on the fish for their livelihood.

Although zebra mussel veligers – the larval form of the shellfish – were first detected in Upper Red Lake in 2018, to date no adult mussels have been found in either basin, making the connected lakes unique among the state’s top walleye waters.

In invaded lakes, perch were found to exceed the .22 parts per million threshold once they reached a length of 8.8 inches. “We’re not sure what’s going on,” said Tyler Orgon, a biologist who works for the tribe. The conditions may not be suitable for the mussels, added Orgon, who theorized that there may not be enough hard surfaces in the lake bed for the mussels to attach to.

“But that’s not to say they won’t take off,” he cautioned. “I think it’s too early to tell.”

For her part, Blinick said she hopes the mercury study will make Minnesotans more vigilant about preventing the further spread of zebra mussels. Currently, she noted, there are no feasible means to eradicate mussels from the 311 lakes in the state they are known to inhabit.

In the course of her three-year research project, Blinick and her colleagues routinely encountered curious anglers at boat landings. “The comment I heard most often was, ‘The zebra mussels make the lake clearer. Don’t we like that?’” Blinick said. “I think that’s unfortunate. I wish we were more effective at getting the message out that this artificial clearing is a bad thing.”

This article first appeared on MinnPost and is republished here under a Creative Commons license.

-

In the new picture book “The Blue House I Loved” Minnesota author Kao Kalia Yang shares vivid memories of childhood and place. Illustrated by artist and architect Jen Shin.

-

There was standing room only for much of the Nevis City Council's monthly meeting on Feb. 9, 2026, as the Council considered continuing its support for a local skate park.

-

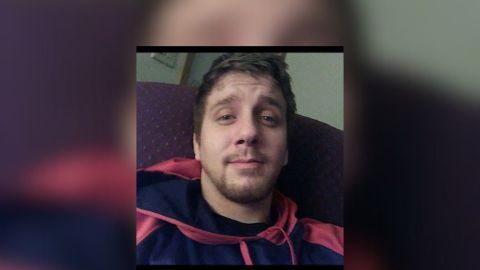

Corey Adam Bryant was last seen in Bemidji on Dec. 19, 2025, but was last in touch with family in January 2026.

-

Events this week include a pancake fundraiser and curling watch parties in Grand Rapids, "MusiKaravan" in Hibbing, Bemidji Contra Dance and a symphony orchestra concert in Virginia.