Our phenology coordinator Sarah Mitchell is off this week, soaking up the sun, chasing frogs, and browsing on blueberries. In lieu of the usual segment summary, she has left us an article about the surprising life of Minnesota's shrews. Never fear, though- you can listen to the phenology talkbacks segment using the 'play' button at the top of the article!

This article was originally printed in the Winter 2022 Cedar Creek Newsletter, and has been lightly edited for this purpose.

——

Mysterious Monsters of the Midwest

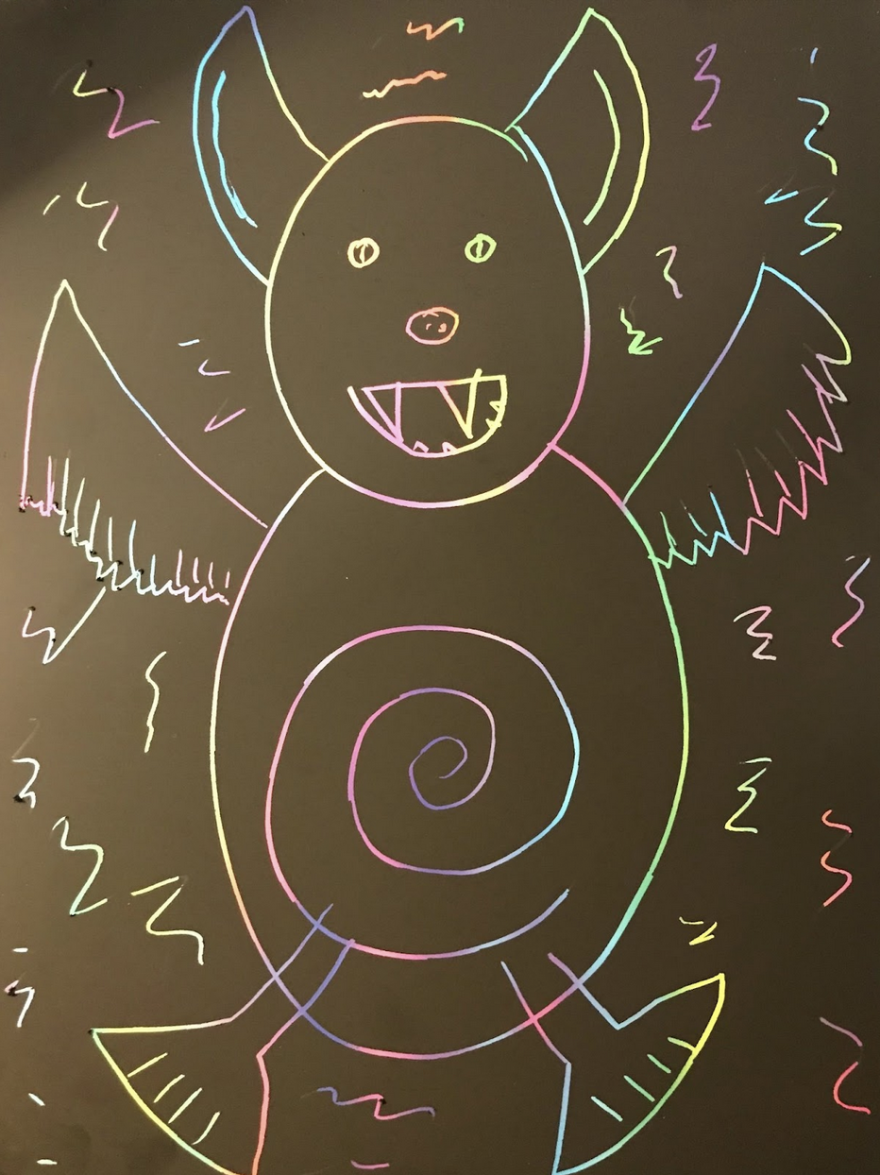

Imagine an animal with a bat’s echolocation, a snake’s venom, and a hummingbird’s heart rate. This creature can also run on water, paralyze its prey, and eat up to three times its weight a day. If you were to draw a picture of it, what would it look like? What color would it be? What evidence would it show of its abilities? When I ask students these questions, they often draw huge, brightly-colored creatures with big ears, fangs, wings, big feet, and a terrifying face. What do you imagine?

Shockingly, we have these mysterious creatures in Minnesota. Despite their impressive and bizarre list of adaptations, they are some of the most unobtrusive mammals found in the state, with an appearance similar to a plain old deer mouse. Minnesotans, I’m happy to introduce you to our native shrews! Minnesota has three species of shrew commonly occurring throughout the state: the masked shrew (Sorex cinereus), the pygmy shrew (S. hoyi), and the short-tailed shrew (Blarina brevicauda). Additionally, the arctic shrew (S. arcticus) and the northern water shrew (S. palustris) live in the northern three-fourths of the state. Rarer shrews include the least shrew (Cryptotis parva) and the smoky shrew (S. fumeus), which are found only in a few counties. Each shrew contains a multitude of evolutionary surprises! Shrews certainly are not very charismatic on the surface, with their small size, drab colors, and generic-rodent-like appearance. However, their plain exterior hides some of the most fascinating combinations of adaptations in the state.

The driving feature of a shrew’s life is its incredibly high metabolic rate. Broadly speaking, shrews are the mammalian version of a hummingbird; their lives are a constant battle to sustain high-energy, calorie-draining activity with a huge quantity of calorie-rich food. Like hummingbirds, shrews are tiny, move fast (they perform up to twelve body movements per second!), have incredibly high heart rates (depending on species, a shrew’s heart can beat at 800-1000 beats per minute), and have a voracious appetite to match. While hummingbirds cope with their high energetic needs by drinking sugar-rich nectar, shrews turn to another calorically-dense eating style: carnivory. Without food, a shrew will only survive 3-4 hours. To sustain their high activity level and ultra-fast metabolism, a shrew needs to eat between one and three times its body weight per day. Also impressive - unlike hummingbirds which fly south for the winter, shrews remain here in Minnesota and stay active throughout the winter. Their tiny bodies lose heat rapidly, further increasing their need for calories when the temperatures are below freezing. They are primarily insectivores, but are opportunistic generalists that won’t turn up their long, agile noses at other prey. They will eat worms, mice, frogs, and will even cannibalize each other if they get a chance. A gory but common sight in basement mouse traps across Minnesota are chewed-up carcasses of trapped mice: shrews view these as ready-made buffets. Meanwhile, in the western United States, shrews can be found following swarms of locusts, just as packs of wolves follow herds of caribou. Some patterns of predation remain true regardless of size!

Over evolutionary time, shrews have adapted to the demands of their high metabolism by gaining a bizarre mix of traits to help ensure a steady supply of food. Shrews are one of the few species of mammals besides bats and dolphins that can echolocate: since they must hunt around the clock, and their eyesight is poor, echolocation enables shrews to find prey no matter the light conditions. In addition, the short-tailed shrew is venomous! Interestingly, it does not inject venom like a snake, but instead chews the venom into the prey, causing paralysis and eventual death. This venom is a fantastic adaptation for these hungry critters: it allows them to take on larger prey, and store (or ‘cache’) their paralyzed but still-living prey for up to 15 hours. In winter, when fresh prey is hard to find, this is an incredibly important adaptation to an unreliable food supply. The venom is strong stuff, as well: a single shrew can have enough venom to kill up to 20 mice. While a few other mammals have venom, such as the slow loris, the platypus, and the vampire bat, shrews are the only known group of mammals that uses venom to paralyze and kill its prey. And although insects, rodents, snakes, and fish may need to watch their step (or slither, or swim), humans have no cause for concern. Envenomated shrew bites in humans are rare, and not fatal. They can however produce a burning sensation, pain, and swelling for a few days.

The northern water shrew, while not venomous, has its own suite of adaptations. This aquatic shrew hunts crustaceans, aquatic insects, fish, and anything else it can get its little teeth into. Key to their success is their feet, which have stiff, comb-like hairs. These hairs act as paddles, enabling the shrew to run distances up to five feet and more on the surface of the water. While diving (the water shrew is the world’s smallest mammalian diver), the stiff hairs act as paddles, helping the shrew move quickly and with agility through the water. Once they return to land, northern water shrews use the hairs as a comb, brushing water out of their fur and distributing an even coating of water-repellant oil.

As far as I’m concerned, a tiny creature with echolocation, venom, and the ability to run on water has plenty of evolutionary ‘super powers’ already. But shrews have yet another trick up their furry little sleeves! In the winter, when food is scarce, they shrink. The shrink does not just come from muscle and fat, but also includes energetically-draining portions of their body like their brain and their liver. This helps reduce the amount of food they need to consume to survive. In the spring, when food is again abundant, they will regrow their organs (though frequently they do not regrow to their original size).

As you might expect from these twitchy, voracious little critters, shrews embrace a ‘fight on sight’ worldview with others. While they do not establish strict territories, they will unhesitatingly pick a fight with any other shrew they come across, as well as with most other critters even close to their weight class. A quick search of “shrew fight” on YouTube will show videos of shrews taking on snakes and scorpions, and even bullying a couple of Russian fishermen for some bait fish (spoiler alert: the shrew is almost always victorious).

A final odd characteristic of shrews regards their reproduction. Some female shrews can get pregnant the day after they give birth, and will be pregnant while raising their first litter. Eventually, the young are ready to leave the nest. Due to their bad eyesight, they are not able to follow each other by sight. Instead, they line up and each bites the tail of the shrew in front of it. As a strange, furry freight train, they follow the mother out into the world!

My first inkling of the weird world of shrews came ten years ago, when I was reading Stan Tekiela’s field guide Mammals of Minnesota for an undergraduate biology class. In addition to identifying features, Stan offered fun facts about the life histories of the different wildlife species. There, I learned that short-tailed shrews had venom and that the northern water shrew could walk on water. My curiosity piqued, I did some googling, and with every new article I found a new peculiar fact about them. I’ve been a lot more fun at biologist parties and a lot less fun at normal parties ever since! For me, shrews act as a great reminder that nothing in nature is as simple as it looks on the surface. Their tiny, drab, mousey-looking bodies hide a bonanza of evolutionary superpowers!