John: I think it's time to talk to Donna! We're talking about the Western prairie fringed orchid, Platanthera praeclara.

Scott: Donna Spaeth is on the line with us this morning.

John: Yes, Donna and I met at a phenology gathering over on the White Oak Reservation at the Tamarac Wildlife Preserve. Donna came along and started talking to me about the phenology that she was doing, and I was captivated! Good morning, Donna.

Donna: Good morning! Yeah, we met over at Tamarac Wildlife Refuge, over here on White Earth Reservation. Where I live is in Mahnomen County, but I work with the western prairie fringed orchid up in Northwestern Minnesota. It’s out on the prairies a little bit further west than where I am.

John: Yeah. So, is this orchid just a prairie plant?

Donna: It’s exclusive to the prairie region and it grows in wet prairie areas. So, it is a prairie plant.

Scott: Last year we had a really dry year. Did the drought do harm to the viability of the orchids?

Donna: My phenology throughout the years with this plant has shown that it is capable of going through drought and it does fairly well. It was dry last year, and it does affect it, but this is a very long-living plant, like a lot of orchids are. It seems to be able to get through it.

John: Interesting. You mentioned in a note to me earlier that this year was unusual because development was kind of idling along as it normally does, and then, toward the end of June, we got some 95-degree weather and boom, things changed! Can you describe what happened there?

Donna: Yes! So, this particular orchid is very responsive to the heat units or how much heat we get. It was a cold and wet spring up here in northwestern Minnesota through much of May and a lot of things were going slow. Then, we got those 90-degree days (it was almost a hundred) and it elongated from 15-20 centimeters to 30-40 centimeters in a week’s time. It was a huge expansion, and then a large pea bud formed. So, then it kind of settled down a bit. My job is to go out and check on this plant and see what it’s doing in the field so we can help gather people to help census every year while it’s blooming. That’s the easiest time to see it and get a good count on what the population is doing.

John: What does it look like when it’s blooming?

Donna: It’s a large white flower with multiple flowers(between 5-25 blossoms). It’s very large; if you’re driving by the prairie, it looks like a white flag standing in the field. That’s the best way to describe it.

John: So, it’s much taller than the surrounding vegetation?

Donna: Not a whole lot. It stands up because the prairie grass will bend and sway (it looks like an ocean of grass). The orchid is a little more stiff. The best way to describe it is that it doesn’t bend with the prairie grasses. There are a few other plants that can kind of catch your eye and look similar to the orchid: spreading dogbane and water hemlock. When we’re out doing census you’re like, “Maybe there’s one over there!”, you go over, and it’s a spreading dogbane, a water hemlock or a death camas (another prairie plant). It’s fun to see all this stuff on the prairie.

John: It surely is fun, I agree! Botany is one of those exciting things. How did you get started in this?

Donna: I think I’ve always been a plant person, but how I actually got started in it was I met Nancy Sather, who’s a retired botanist from the Minnesota DNR. She had posted an article in the Minnesota Volunteer [Magazine]. Oh my gosh, this has been a long time ago! I’m going to date myself. It was back in 1996!

John: Oh yeah! Back when Scott and I were in our fifties!

Donna: Yeah! It was with a different plant; she was looking for the Cooper’s milkvetch which in certain areas is not very common. I happen to live in an area where it’s pretty common, and sent her a picture (back when we had 35mm film before all of this digital!). It took a while, but I met her through that plant and she discovered that I had a real talent for seeing detail, especially in plants. Then she invited me to come and help her with the orchid census and do some demography, and she discovered that I was very good at it. Because I live up in this region and it’s a little closer than Minneapolis, I became their Northwest contact to go out and do phenology. Now I’ve been contracted as an actual field botanist to go out and monitor the plants through the contract. It’s been a long time and I really enjoy it. It’s like my staycation job away from my real job as a farming/ranching person.

Scott: Neat! Donna, the orchid is endangered. Why is that?

Donna: Well, in Minnesota, it’s listed as endangered. In the United States, it’s a federally threatened, species, and in Canada, it’s a federally endangered species. It lives in a region where there’s been a lot of habitat loss through the settlement of North America. It’s in a prairie region where it’s good farmland as well. It has a very specialized habitat it needs to grow in, and not a lot of the prairie is wet (it’s a wet prairie plant, as I described before). It has this very specialized habitat, and the habitat has been fragmented over the course of the settlement of North America. That’s why it’s endangered.

John: Are you seeing any new plants that are coming up, that are creating viable seeds and actually expanding [their range] now that you’ve honed in on them and are aware of them? Once you find them, are you able to get farmers to not plow that area? How does that work?

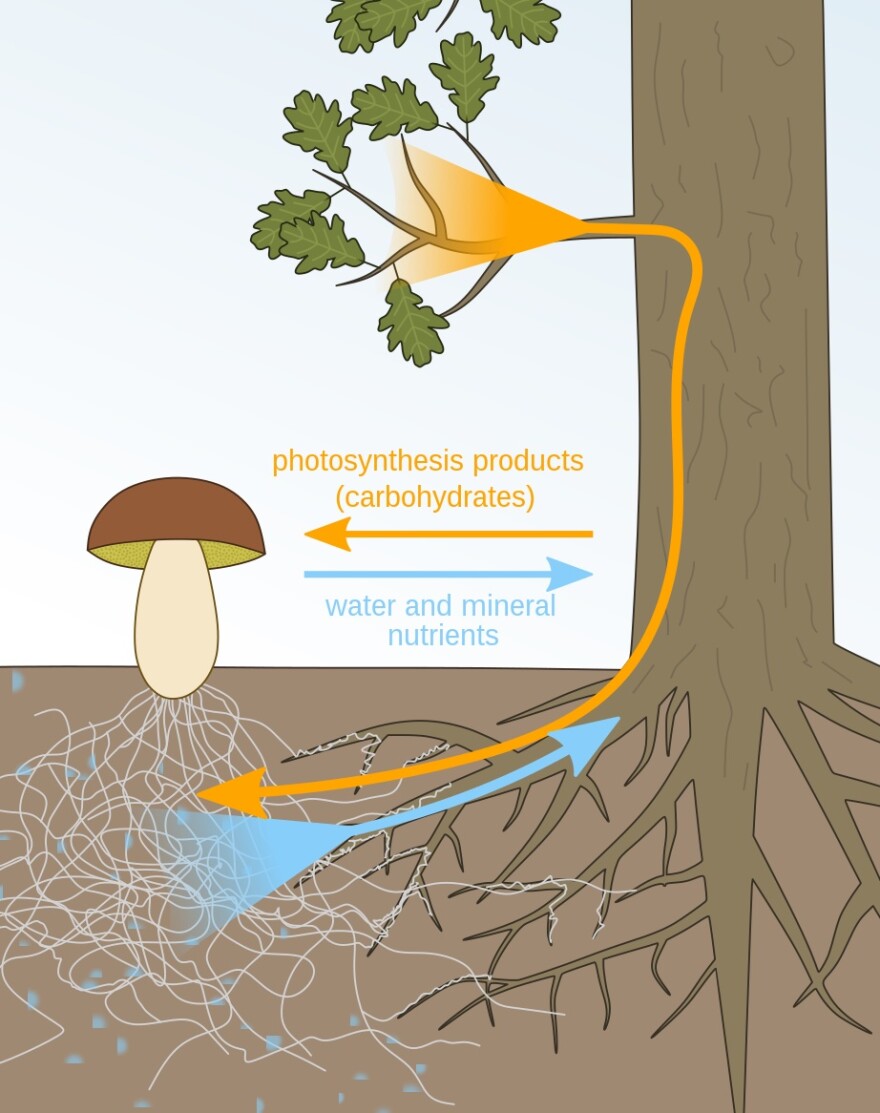

Donna: Those are questions that would be better answered by the DNR botanist. I would recommend Derek Anderson. They do a lot of studies about it. It does produce viable seed, but as far as I know it wouldn’t be viable in a habitat like an unplowed field that’s been put into CRP. Like all orchids, it’s very dependent on symbiotic mycorrhizae [specialized species of fungi that pair up with plant root systems to provide vitamins and minerals in exchange for sugars and energy]. They require those mycorrhizae to even germinate. For this orchid, conditions have to be absolutely right. It does produce viable seed, but the seed (as with all orchids) isn’t a full seed with the protein in it to make it grow from the seed alone. It has to connect with the mycorrhizae. It spends time underground and developing for up to several years before it even emerges. It’s pretty amazing that this plant can develop. Over the years, I’ve done demography and I have seen and found first-year emergent plants. They’re very, very tiny, only three millimeters wide and seven to ten millimeters long in a whole sea of grass.

John: My gosh!

Donna: That’s what I get to help find!

Scott: Donna, you said that the CRP (conservation reserve program, which pays farmers to not cultivate land) wouldn’t necessarily guarantee a regeneration, but are the areas they exist now protected?

Donna: Yes, as far as I know most known populations are either in a wildlife refuge area, a waterfowl production area, the Nature Conservancy is a partner that works with the Fish and Wildlife in the Minnesota DNR, or a SNA [scientific and natural area] program. Those areas are protected through some sort of non-development agreement. They’re going to be prairie forever, not just for the orchids but other wildlife and habitat that is needed out there on the prairie.

John: You mentioned in your note that a census was coming up. Is that something that our western edge listeners, or someone who just wants to, could go and help out? Is that open to people?

Donna: Yeah, the census is open to the public. It’s very dependent on citizen scientists (a good name for people who just want to help do projects like this). I mentioned Derek Anderson; he’s the one who helped gather volunteers for this particular species. I hope you can share his contact information. People who are orchid enthusiasts and live out on this western prairie region (or want to come over from the east side), contact Derek Anderson. This is going to take place this weekend [July 9-10]. That’s where my phenology trips help us decide, “are we going last weekend or are we going this weekend?”. The western fringed prairie orchid usually blooms around the 4th of July. I’m certain it’s blooming right now [July 5th], but to get the best census it’s best to go at peak bloom. From my phenology that I was doing, I’m going to say the peak bloom is probably going to be throughout this weekend and into next week.

Scott: Is the census done every year?

Donna: Yes, it’s done every year. Once people sign up with Derek to be a volunteer, then he puts you into a regular email list and contacts regular volunteers every year.

Scott: And how wide a range are we talking about? Is it a huge square mileage area or is it in small, isolated spots?

Donna: The census is done in small areas, but the range of the western fringed prairie orchid goes from Manitoba all the way into North Dakota and Iowa. It does have some places in Nebraska, some small pocket populations, but the census population here in Minnesota is done in the Polk County region.

John: Donna, thank you so much for joining us this morning. It was a real treat to talk to you and to hear about the phenology of the western prairie fringed orchid. I want to thank you again for joining us and I hope you guys have the greatest success. Maybe find some new plants to add to the list!

Donna: Thank you, John, I appreciate it.