RED LAKE — Connecting with nature is part of the Anishinaabe way of life, and on the Red Lake Nation, a charter school is seeking to help foster that connection, incorporating Ojibwe language and tradition with the seasons.

Red Lake's first charter school recently partnered with the Nature Conservancy for the purchase of a new pontoon to take environmental learning out of the classroom.

The nonprofit’s Tribal Relations Coordinator John Littlewolf is of the Bois Forte Band with ties to the Cass Lake area. He said the goals of the Nature Conservancy align well with the priorities of the Red Lake Nation.

“Peatlands, water quality, science and monitoring — these are our specialties at the Nature Conservancy [and] it is a natural fit with the Red Lake Nation on so many fronts,” Littlewolf said. "These students are going to be able to experience something that I wish I would have had this opportunity going to school: to be able to get the classroom out onto the water.”

During the inaugural pontoon outing on Fuller’s Lake Wednesday, Nov. 12, a handful of charter school families braved the cool November weather for boat rides and hot chocolate.

Fuller’s Lake is tiny compared to the nearby Lower Red Lake but features interesting islands and some underwater caves. The charter school’s executive director Nate Taylor said he was reminiscing about special memories while taking the cruise.

“We grew up playing all through this area," Taylor said.

“I almost drowned in this lake when we were kids. We swam all the time here. It just was one of those epiphany moments, like we were just in the moment, and you're really happy. And I started singing a song because I was remembering him.”

Taylor said the song he was gently singing above the roar of the pontoon motor was one he wrote for his younger brother, who died young from juvenile diabetes.

Fuller’s Lake is just a couple of miles away from the charter school and will be one of the many water bodies within the Red Lake Nation the students will explore with their new equipment.

“We wanted to know about almost every single tree that's out there, every single plant that's out there, every single — because we did know at one point — fish that's out there," Taylor said. “This boat will give us the opportunity to get kids out on the water and get in to learn about Mother Nature, from a perspective that you don't really get to if you don't have a boat.”

Endazhi-Nitaawiging is the name of the Ojibwe-language intensive charter school for grades K through 8. It translates from Ojibwe to “where it grows.” Kindergartners and first graders experience more Ojibwe immersion than older students, but the entire school’s curriculum is closely tied with language and seasonal traditions.

“There are types of seasons when we gather wild rice, type of season we gather blueberries, strawberries, maple syrup,” Taylor said. “I think it's our moral responsibility to do that and to get our kids to do that, because our people always thought seven generations down the line. And our ancestors thought of us, and that's why I feel like Red Lake is so strong. And we have to keep that ball rolling and think of them in the future.”

The school maintains an enrollment of about 100 students, with more information on its website.

Taylor said the school, initially chartered four years ago, stemmed from a decade of dreams that began with a pre-K program, called the Waasabik Ojibwe Immersion School.

“This school kind of evolved from that because we were teaching kids the language at three and four years old, but you need to keep on them," Taylor said. “Because at that school, it was only four hours for four days.”

Indigenizing education is key to the mission, Taylor said. The U.S. and Canada’s prior policies of residential boarding school systems frequently took Indigenous students out of their communities, where they were punished for speaking Indigenous languages or for practicing traditional customs, like boys wearing long hair, in addition to suffering other abuses.

“My wife and I had some first-hand experience: We went to Haskell Indian Nations [University], and it's a college that's built on an old boarding school,” Taylor said. “So you can see the evidence of what happened, using child handcuffs and different things, a historical center there of what happened.

“There was railroad tracks, and they would ship us in like cattle, and a little bit of the history of what happened to our people and why we don't speak our language.”

The residential boarding school system’s sole objective was to “civilize” Indigenous children to mainstream American culture, and they were first established in the late 1800s. The U.S. government originally mandated attendance at these schools, and generations of passed-down Indigenous wisdom were almost wiped out.

Native American students continue to face several challenges within the American education system.

The Indigenous Foundation cites figures from the Kids Count Data Center and the National Violent Death Reporting Center showing Native students are more likely to be behind in reading and math, more likely to be suspended and twice as likely to drop out of school altogether, compared to students of other demographics.

Endazhi Nitaawiging’s Director of Academics Rochelle Johnson said the school takes a more holistic approach to education.

“One of the main goals is to really make sure that the school feels like a second home to our students,” Johnson said. “We develop a strong sense of belonging, a strong sense of who they are as young Native people in the community, and we're really community-based, and practice local culture and teach that.”

-

Crow Wing County's Eric Klang said agents worked out of the sheriff's office while temporarily stationed in the lakes area, asking him for guidance on "what's off limits."

-

Plus: Community members show up to Nevis council in support of Wild Tiger Skate Park; House 2A Rep. Bidal Duran announces reelection plans; and the latest for Northland winter athletes.

-

Crow Wing County's Eric Klang said agents worked out of the sheriff's office while temporarily stationed in the lakes area, asking him for guidance on "what's off limits."

-

There was standing room only for much of the Nevis City Council's monthly meeting on Feb. 9, 2026, as the Council considered continuing its support for a local skate park.

-

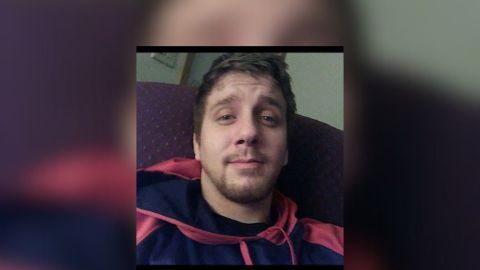

Corey Adam Bryant was last seen in Bemidji on Dec. 19, 2025, but was last in touch with family in January 2026.

-

Plus: Northern, MN to become Northern MN's newest city; and 14 Northland athletes competed in the Alpine Ski state tournament Feb. 10, 2026.

-

Minneapolis businesses are estimated to have lost $10 to $20 million in sales each week of Operation Metro Surge, which began in December 2025.

-

An administrative law judge ruled in favor of the township's petition to become a city while denying Bemidji's counterpetition to redraw its boundary around Lake Bemidji.

-

The School Board voted down the alternative schedule 4-2. In the coming months, the district will have to figure out how else to cut 12% of its budget.

-

Three rural Northern Minnesotans placed at the state alpine ski meet in Biwabik on Feb. 10, 2026.